The way I recommend using git in a dev team

2022-03-11

Looking back at my old git commits reveals an entertaining, if slightly embarassing mess.

$ git log --oneline -10 --author jcreek --before "Wed Nov 5 2014"

8b6d283 Updated instructions

6b271ba Undid that last change

8c4f48a MySQL -> MySQLi changes begun

c07ae83 Fixed that bug

e5ab087 Some small cosmetic changes and failed fix of bug

4467af9 Updated to-do list

3578065 Cleanup and to-do list

ddefa3a Added admin tools, provided link to admin page

8a2f8b6 Further admin tools

63cc797 Unimportant changes

The contrast with more recent commits is staggering.

$ git log --oneline -13 --author jcreek --before "Wed Sep 1 2021"

c05c2c5 build(CAN-186): Add missing package information to csproj

06aca19 docs(CAN-190): Add documentation to StringHelper

4600ebf (tag: 1.0.1) feat(CAN-182): Add filename validity checks to SftpRepository

d80cc82 (tag: 1.0.0) chore(CAN-173): Update readme and licence for NuGet

615994a refactor(CAN-215): Rename to Creek.FileRepository

0fe9924 feat(CAN-171): Add all repositories to factory

b22d2f7 feat(CAN-170): Add base implementations of all repositories

952a9a9 refactor(CAN-211): Rename FileName to Filename in interface

62665fe test(CAN-169): Add SftpRepositoryShould tests

ebccd4a feat(CAN-168): Add GenerateStreamFromString helper method for testing

82fd258 fix(CAN-135): Initialise content with a new stream so it can be written to

4232dd9 fix(CAN-162): Add missing throw to ensure exceptions get passed up the stack

26a953d feat(CAN-167): Add initialiser for SftpRepository to use an IConfiguration

My recent commits follow a clear convention, are concise and clear at a glance. Without having to do any code comparison you can quickly assess what was done in any given commit. A commit message shows whether a developer is a good collaborator, with good ones reducing the need to re-establish the context of a commit as much as possible.

I never used to care about my commit messages because it was only me reading them, and because I rarely, if ever, used tools like git log, git blame, revert or rebase. Nowadays I use git blame all day, every day, thanks to VSCode git extensions putting the blame on every line of code, and it's incredibly useful as part of a team. If I'm looking at code I always know who worked on it, when they worked on it, and the context of why they did what they did, which makes the codebases infinitely more maintainable.

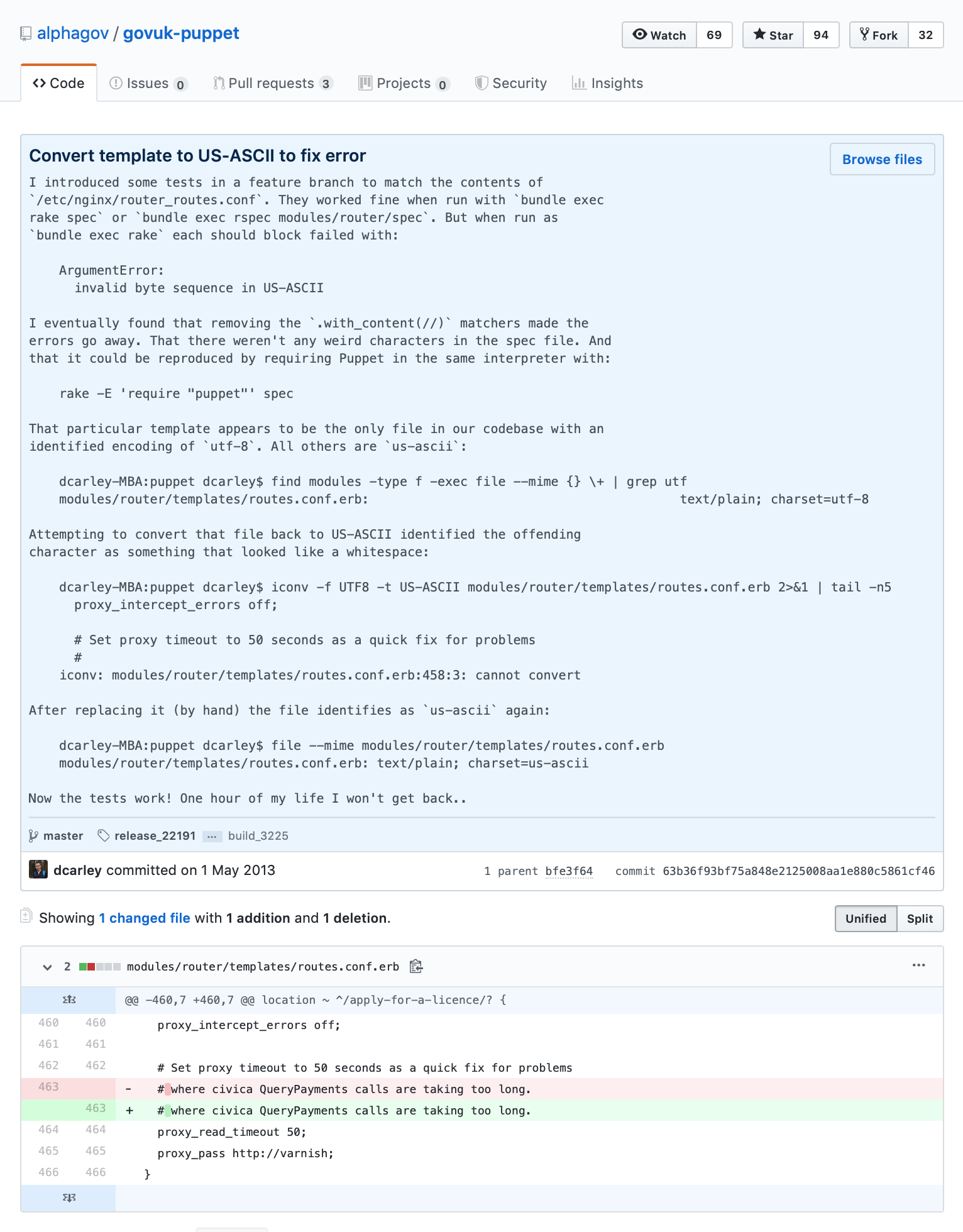

There is a single git commit that I think should be required reading for all developers. It is from a developer by the name of Dan Carley working on GOV.UK, and it has the rather unassuming name of "Convert template to US-ASCII to fix error".

I found it through this blog and I'd highly recommend reading through it, but essentially the thing I like most about this commit is it explains why the change was made, not just what the change was.

As with most developers, I have my own strong opinions founded in habit for what dev teams should do in terms of Git usage. In the rest of this doc I will outline that - let me know if you have any suggestions for improvements, or if it helped you.

Branching, Pull Requests & Merging

For every ticket, there should be a separate git branch. This code will not be merged into the main development branch until it has been through a pull request and been reviewed.

If it's a big feature ticket, a feature branch should be created for that ticket, and it should be split into sub-tasks, each of which have their own branch and get merged into the feature branch after PRs are approved. Once all the sub-tasks have been PRed and their branches have been merged into the feature branch, the feature branch can be PRed and merge into the development branch. If you find you're needing to do all your changes in one branch, do so, then split it up by making new branches and cherry-picking or re-committing once you have your finished code. This will make it significantly easier to review, and to review well.

Unless you're working on a sub-task branch, the merge strategy for PRs should involve squashing. Merge commits are fine, and they leave all individual commits available for comparison, reverting and cherry-picking, but they also include all of the ongoing dev work and changes based on PR feedback, which can clutter up a project.

Not using squashed commits makes having good quality commit messages even more important. Committing often and messily is a bad habit (unless you're squashing). Instead break down tasks into suitably small sub-tasks, so that they can be worked on in isolation without taking long enough to warrant committing unfinished code.

A key part of the PR process is reviewing code, not only for bugs, but for quality. The git commit messages are a critical part of this. No developer is perfect, so helping one another in PRs is key to having an excellent git history. If a PR comes in with bad commit messages, it should be rejected and redone with good commit messages.

Git Messages

Git commit messges subjects should always follow this pattern:

<type>(scope): <description>

Types are:

build: build-related changesci: continuous integration-related changeschore: updating grunt tasks etc; no production code changedocs: changes to the documentationfeat: new feature for the user, not a new feature for build scriptfix: bug fix for the user, not a fix to a build scriptperf: a code change that improves performancerefactor: refactoring production code, eg. renaming a variablerevert: reverting thingsstyle: formatting, missing semi colons, etc; no production code changetest: adding missing tests, refactoring tests; no production code change

The scope, generally considered optional, really should be mandatory. Typically this would be a ticket number, enabling devs both now and in the future to easily find commits associated with tickets and tickets associated with commits. Full details of what was being worked on can often be found in a ticket if they are not in the commit message, and in the event a feature's code needs to be examined or reverted. If you use a ticket management system like Jira having the ticket number in your commit message enables the management system to automatically detect it and it can be embedded directly in a card that you are currently working on, and even associated with Pull Requests and Epics.

The description is also incredibly important. A properly formed description should always be able to complete the following sentence:

If applied, this commit will <description>

It contains a succinct description of the change:

- Use the imperative, present tense: "change" not "changed" nor "changes"

- No full stop/period at the end

The body of a commit message should also use the imperative, present tense: "change" not "changed" nor "changes". The body should include the motivation for the change and contrast this with previous behavior.

The 7 rules of a great commit message:

- Separate subject from the body with a blank line

- Limit the subject line to 50 characters

- Summary in the present tense. Not capitalized.

- Do not end the subject line with a period

- Use the imperative mood in the subject line

- Wrap the body at 72 characters

- Use the body to explain what and why vs. how

By incorporating the above convention, you can quickly determine what changes have been made and what the commit message for the changes would look like. With that format, you as a developer can immediately know (or at least guess), what’s changed in the specific commit. If there’s an issue with a new merge to the master branch, you can also quickly scan the git history to figure out what changes possibly can cause the problem without the need to look at the differences.

Some very good reasons to use this convention are:

- Automatically generating CHANGELOGs.

- Automatically determining a semantic version bump (based on the types of commits landed).

- Communicating the nature of changes to teammates, the public, and other stakeholders.

- Triggering build and publish processes.

- Making it easier for people to contribute to your projects by allowing them to explore a more structured commit history.

Code Reviews (in PRs)

When reviewing code, here are the key things to be paying attention to:

- Refactoring to remove old/inefficient/not working code: Ensure that the code changes include removal of redundant or outdated code snippets. Refactoring should improve the code's efficiency, readability, and maintainability without altering its functionality.

- Code style: Review for consistency with the project's coding standards. This includes adherence to naming conventions, file organisation, indentation, and comment quality. Consistent code style aids in understanding and maintaining the code base.

- Code smells: Look for indicators of deeper problems in the code, such as duplicate code, long methods, large classes, and improper use of object-oriented principles. These "smells" can indicate areas that may need refactoring.

- Best practices and design patterns: Check if the code follows established best practices for the language and framework being used. Verify the appropriate use of design patterns which can help in solving commonly occurring problems in a more efficient way.

- Performance considerations: Analyze the changes for potential performance issues, such as memory leaks, inefficient algorithms, and unnecessary database queries. The goal is to ensure that the new code does not introduce performance regressions.

- Security aspects: Evaluate the code for security vulnerabilities. This includes checking for SQL injection, proper handling of user data, adherence to authentication and authorization mechanisms, and ensuring data privacy.

- Testing: Ensure that the new code includes relevant unit tests or integration tests that cover the new functionality and any changes to existing functionality. Good test coverage is essential for maintaining code quality over time.

- Documentation: Verify that any new methods, classes, or significant logic changes are accompanied by appropriate comments or documentation. This is crucial for future maintainability, making it easier for others to understand the purpose and functionality of the code.

- Overall code quality and readability: Assess the overall quality of the code. The code should be readable, well-organized, and logically structured. It should be easy for someone else on the team to understand and maintain.

Remember, as a code reviewer, you are responsible for ensuring the quality and integrity of the code base. Your review can help prevent issues and improve the overall quality of the software. Therefore, it's important to be thorough and provide constructive feedback during the review process. A reviewer is equally responsible for any bugs or issues found in after a PR has been approved and merged. If a PR is too big or complex to reasonably review well, reject it and flag this to the developer who submitted it. Where possible you should test the branch, but at the very least any UI changes should be demonstrated via a screenshot or gif in the description of the PR.

Automating Git Commit Message Formatting

You can tell git to set up your commit messages with a set structure. This is done by running the command git config --global commit.template ~/.gitmessage or by manually setting commit.template in ~/.gitconfig using your text editor of choice:

Next, create ~/.gitmessage with your new default template.

For your convenience, the following git commit template can be used:

# A properly formed Git commit subject line should always be able to complete

# the following sentence:

# * If applied, this commit will <description>

#

# ** Example:

# <type>(scope): <description>

#

# [optional body]

#

# [optional footer]

# ** Type

# Must be one of the following:

# * build: build-related changes

# * ci: continuous integration-related changes

# * chore: updating grunt tasks etc; no production code change

# * docs: changes to the documentation

# * feat: new feature for the user, not a new feature for build script

# * fix: bug fix for the user, not a fix to a build script

# * perf: a code change that improves performance

# * refactor: refactoring production code, eg. renaming a variable

# * revert: reverting things

# * style: formatting, missing semi colons, etc; no production code change

# * test: adding missing tests, refactoring tests; no production code change

# ** Subject

# The subject contains a succint description of the change:

# * Use the imperative, present tense: "change" not "changed" nor "changes"

# * No full stop/period at the end

# ** Scope

# A scope should be provided to a commit’s type if possible, to provide additional contextual information

# and is contained within parenthesis, e.g. feat(JIRA-1234): Add NewGitDocumentation endpoint

# ** Body

# Just as in the subject, use the imperative, present tense: "change" not "changed" nor "changes".

# The body should include the motivation for the change and contrast this with previous behavior.

# ** Rules

# The 7 rules of a great commit message

# 1. Separate subject from body with a blank line

# 2. Limit the subject line to 50 characters

# 3. Summary in present tense. Not capitalized

# 4. Do not end the subject line with a period

# 5. Use the imperative mood in the subject line

# 6. Wrap the body at 72 characters

# 7. Use the body to explain what and why vs. how